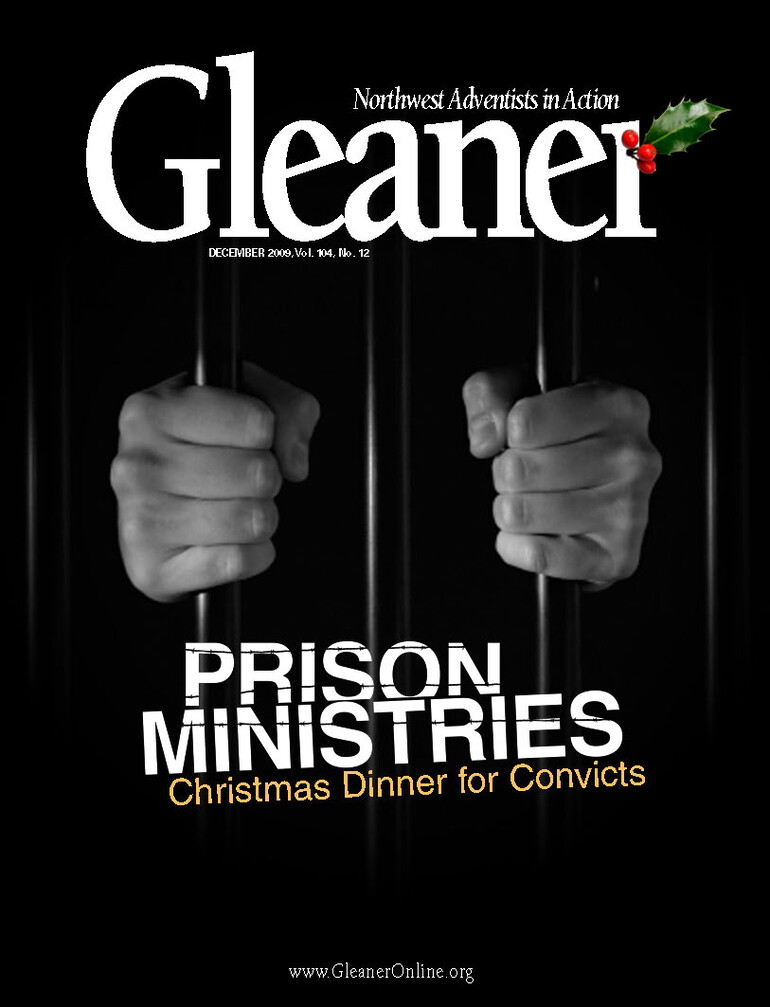

Senator John McCain of Arizona remembers hell on earth, for five and a half interminable years as prisoner of war of the North Vietnamese, as he and his fellow prisoners existed from one nightmarish day to another (those who didn't die, that is).

But then came one unforgettable Christmas Eve . . .

O come, all ye faithful, joyful and triumphant . . .

We sang little above a whisper, our eyes darting anxiously up to the barred windows for any sign of the guards.

"Joyful and triumphant?" Clad in tattered prisoner-of-war clothes, I looked around at the two dozen men huddled in a North Vietnamese prison cell. Light bulbs hanging from the ceiling illuminated a gaunt and wretched group of men — grotesque caricatures of what had once been clean-shaven, superbly fit Air Force, Navy and Marine pilots and navigators.

We shivered from the damp night air and the fevers that plagued a number of us. Some men were permanently stooped from the effects of torture; others limped or leaned on makeshift crutches.

O come ye, o come ye to Bethlehem. Come and behold him, born the King of angels . . .

What a pathetic sight we were. Yet here, this Christmas Eve 1971, we were together for the first time, some after seven years of harrowing isolation and mistreatment at the hands of a cruel enemy.

We were keeping Christmas — the most special Christmas any of us ever would observe.

There had been Christmas services in North Vietnam in previous years, but they had been spiritless, ludicrous stage shows, orchestrated by the Vietnamese for propaganda purposes. This was our Christmas service, the only one we had ever been allowed to hold — though we feared that, at any moment, our captors might change their minds.

I had been designated chaplain by our senior-ranking P.O.W. officer, Colonel George "Bud" Day, USAF. As we sang "O Come, All Ye Faithful," I looked down at the few sheets of paper upon which I had penciled the Bible verses that tell the story of Christ's birth.

I recalled how, a week earlier, Colonel Day had asked the camp commander for a Bible. No, he was told, there were no Bibles in North Vietnam. But four days later, the camp commander had come into our communal cell to announce, "We have found one Bible in Hanoi, and you can designate one person to copy from it for a few minutes."

Colonel Day had requested that I perform the task. Hastily I leafed through the worn book the Vietnamese had placed on a table just outside our cell door in the prison yard. I furiously copied the Christmas passages until a guard approached and took the Bible away.

The service was simple. After saying the Lord's Prayer, we sang Christmas carols, some of us mouthing the words until our pain-clouded memories caught up with our voices. Between each hymn I would read a portion of the story of Jesus' birth.

And the angel said unto them, Fear not: for, behold, I bring you good tidings of great joy, which shall be to all people. For unto you is born this day, in the city of David, a Savior, which is Christ the Lord.

Captain Quincy Collins, a former choir director from the Air Force Academy, led the hymns. At first, we were nervous and stilted in our singing. Still burning in our memories was the time, almost a year before, when North Vietnamese guards had burst in on our church service, beaten the three men leading the prayers, and dragged them away to confinement. The rest of us were locked away for 11 months in three-by-five-foot cells. Indeed, this Christmas service was in part a defiant celebration of the return to our regular prison in Hanoi.

And as the service progressed, our boldness increased, the singing swelled. "O Little Town of Bethlehem," "Hark, the Herald Angels Sing," "It Came Upon the Midnight Clear." Our voices filled the cell, bound together as we shared the story of the Babe "away in a manger, no crib for a bed."

Finally it came time to sing perhaps the most beloved hymn:

Silent night, Holy night! All is calm, all is bright, . . .

A half-dozen of the men were too sick to stand. They sat on the raised concrete sleeping platform that ran down the middle of the cell. Our few blankets were placed around the shaking shoulders of the sickest men to protect them against the cold. Even these men looked up transfixed as we sang that hymn.

Round yon virgin mother and child. Holy infant so tender and mild, . . .

Tears rolled down our unshaven faces. Suddenly we were 2000 years and half a world away in a village called Bethlehem. And neither war, nor torture, nor imprisonment, nor the centuries themselves had dimmed the hope born on that silent night so long before.

Sleep in heavenly peace, sleep in heavenly peace.

We had forgotten our wounds, our hunger, our pain. We raised prayers of thanks for the Christ child, for our families and homes, for our country. There was an absolutely exquisite feeling that all our burdens had been lifted. In a place designed to turn men into vicious animals, we clung to one another, sharing what comfort we had.

Some of us had managed to make crude gifts. One fellow had a precious commodity — a cotton washcloth. Somewhere he had found needle and thread and fashioned the cloth into a hat, which he gave to Colonel Bud Day. Some men exchanged dog tags. Others had used prison spoons to scratch out an IOU on bits of paper — some imaginary thing we wished another to have. We exchanged those chits with smiles and tearful thanks.

The Vietnamese guards did not disturb us. But as I looked up at the barred windows, I wished they had been looking in. I wanted them to see us — faithful, joyful and, yes, triumphant.

Reprinted by permission of Joe Wheeler, editor/compiler of Christmas in My Heart 12, 2003 (P.O. Box 1246, Conifer, CO 80433) and Review and Herald Publishing Association, Hagerstown, MD 21740.