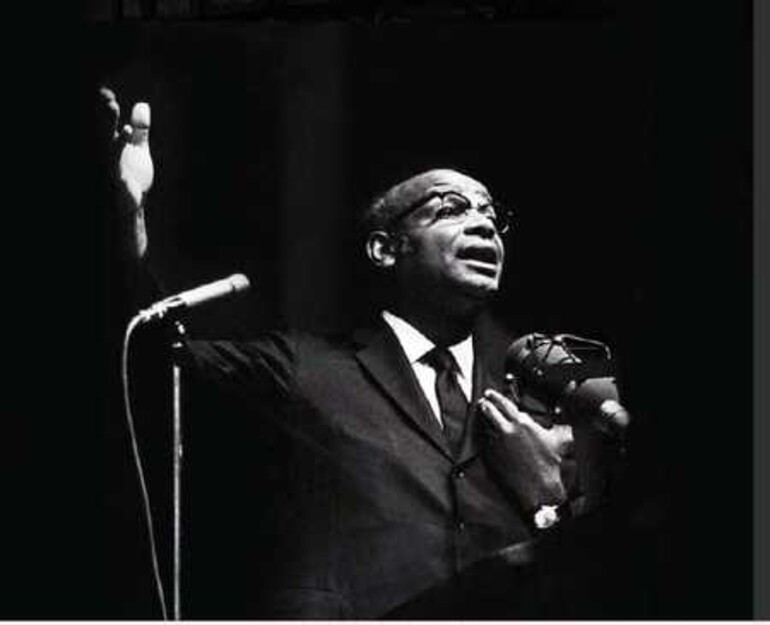

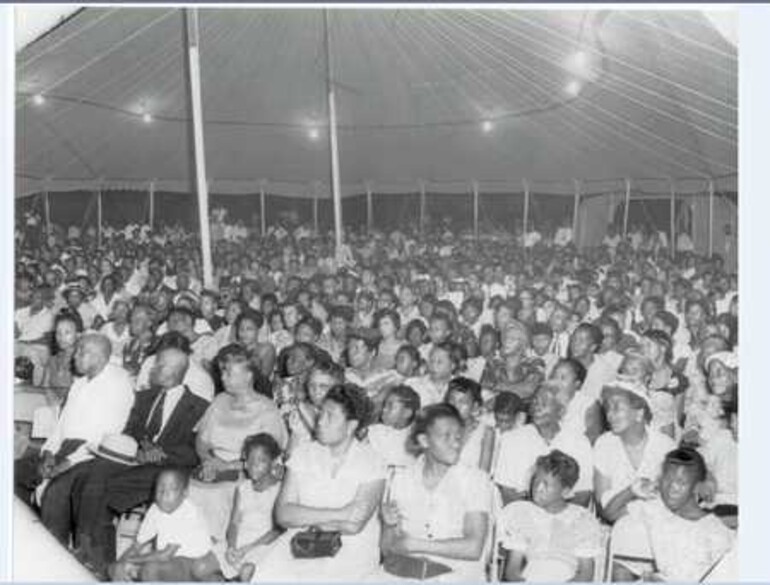

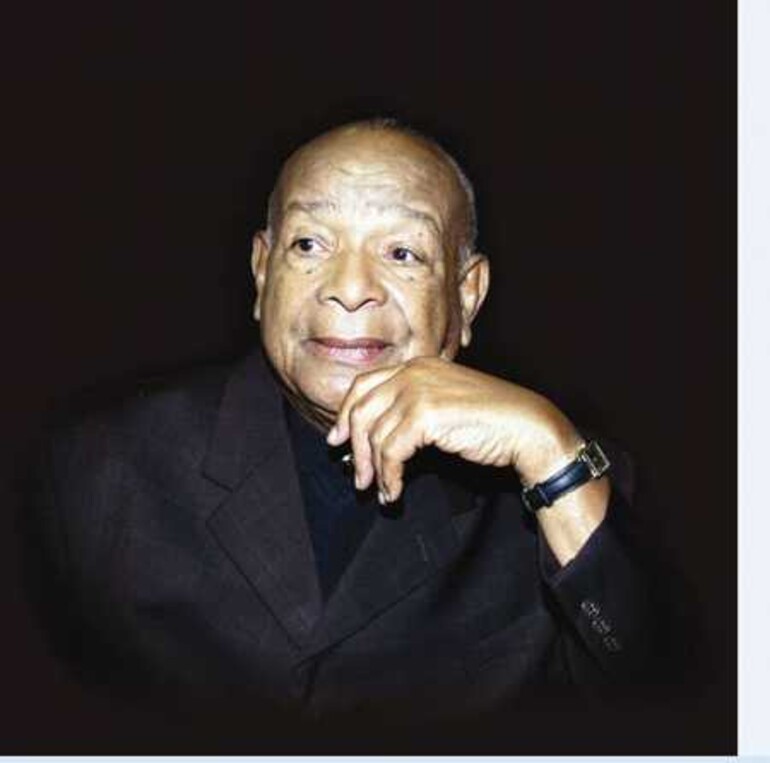

It wasn't the makings of a novel, but an Adventist evangelistic series. In 1954, a young, dashing minister, Edward Earl Cleveland, set up a large tent in the middle of Montgomery, Alabama's, crime "infested" district, across from a night club on Smythe and High streets.

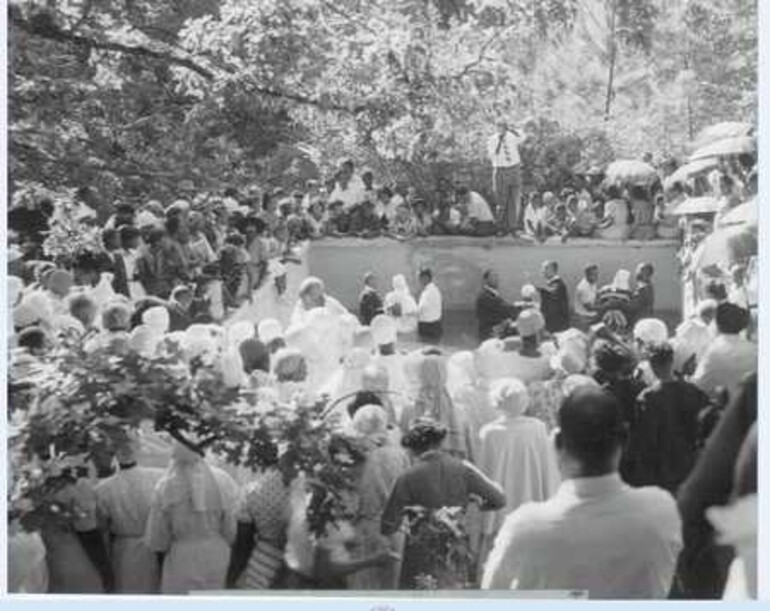

Headlines screamed: "Political Tensions," "Squad Cars Outside," "People Fear for Safety." Our country was in civic unrest and Montgomery city ordinances forbade the assembly of blacks and whites together. However, Cleveland launched the meetings calmly, assuring goers they were children of the King — therefore breaking no law. When policemen walked up and down the aisles, Cleveland said "No need to worry; let the officers do their jobs."1,2 Masses flocked to his tent from across city lines. Participants witnessed "spiritual victories and remarkable instances of divine healing."3 The same account says at the first baptism, "eight giant Trailway buses lined up to transport the candidates to an outdoor swimming pool..." Years later — the wake of what was happening would be called the "the Cleveland Evangelic Explosion." Also in attendance, for at least one night, was a local seamstress — Rosa Parks."4 (It would be a year before Parks would take her stand on the bus.)

Simultaneously, two young ministers from the same city were on vacation and called by their trustees to come home, because a young black "Billy Graham" was stealing their sheep. The ministers raced back and stood outside the tent convocation eyeballing their competition. Hence, the meeting between Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Dr. E.E. Cleveland commenced at an "Adventist tent meeting."1

When they met, King said "I heard a young ‘Billy Graham had come to town, but all I heard was ‘the law, the law, the law.'"

Undaunted and non–apologetic, Cleveland retorted, "You must have arrived late, because I preached "‘the Lord, the Lord, the Lord.'" 1

Mutual respect ensued, and thus began a lasting friendship. Later, (in part to this friendship), King, spoke at Oakwood College in 1962.

As Cleveland's six-month-long crusade drew on, the weather grew colder. More than 3,000 people arrived on any given evening. At this point, Cleveland, being an ever–hopeful optimist, asked only for heaters to keep tent attendees warm.

In spite of this adversity, church records indicate, by December 24, Christmas Eve, the 35–member church, mushroomed into 500 baptized members. Leaders erected a new church building to house the budding membership.3 That same year, Cleveland was elected associate ministerial secretary for the General Conference — a first for his race. Here he integrated a whole department within the GC, where the church headquarters itself was still grappling with issues of racial equity. Whether it was church temperance, community services or inter-city evangelism, Cleveland couldn't separate biblical and civic responsibilities and he left traces of this on every continent but Antarctica. Yet he did this non-combatively, even golfing with the heads he wished to turn. But "he was always straight to the point," said a colleague.5

Cleveland used his involvement in King's organization, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, ... to combine "... soul-winning with concern for social justice..." says Harold Lee in a chronicle of Cleveland's contributions to the Seventh-day Adventist Church. 2

When King was assassinated in 1968, the event came just prior to the Poor People's March on Washington D.C. There was chaos in the aftermath of King's assassination and an outbreak of civil unrest in Washington D.C., leaving thousands of marchers, coming into the city for several weeks, without food or shelter. Cleveland appealed to the GC president and others for basic aid for the marchers.2

Church "[leaders] would have preferred to distance the church from the civil rights turmoil of the 1960s. But ...[He] ... helped nudge the traditionally conservative leadership," says Charles Bradford, former North American Division president.5

The church then "provided the much-needed supplies and organization to help make that march a success," said the late Reger C. Smith.4 Cleveland secured the 18–wheel tractor–trailer that served as a supply base for blankets and clothing for the march. In all the church appropriated $15,000 for the march and received praise for civically being ahead of their time.2

Recently the Adventist News Network reported the death of E.E. Cleveland, an 88-year-old church leader who died after 67 plus years service on August 30.

* Editor's Note: Years later, and from softer seats, we sometimes attach labels. One label that comes to mind might be — Courage.

* Cleveland described his involvement in the civil rights movement. (See his hour-long sermon on the Religious Liberty TV post delivered during Black History Month on Feb. 11, 2006 and archived @ Yahoo!7 Video.)

Special thanks to: 1. Christina Newman, my mother, for finding the first link. 2. Dr. Harold Lee, E.E. Cleveland Evangelist Extraordinary, author, for providing original manuscripts. 3. Steven Norman II, Southern Tidings editor, for providing photos and releases.

1 Sepulveda, Ciro, The Tent and the Cathedral: White-Collar Adventists and Their Search for Respectability, Adventist History Library Weblog, http://bit.ly/alwow, accessed August 31, 2009.

2 Dr. Harold Lee with Monte Sahlin, E.E. Cleveland: Evangelist Extraordinary, Published by the Center for Creative Ministry, 2006.

3 Various contributors, "Black SDA News," Web posts pages 1–4, August 27, 2004.

4 Reger C. Smith Jr., "Perspective: Rosa Parks, Civil Rights Pioneer, Touched Adventist Lives in Her City," Adventist News Network post pages 1–2, November 2005.

5 Unknown, Al.com, "SDA Leader, Teacher E.E. Cleveland Dies at 88," Web posts pages 1–3, September 16, 2009.