This year marks the 100th year for the beginnings of gospel ministry among African Americans on the Pacific Coast. Throughout the century black evangelism and church growth in the Northwest have faced a myriad of challenges including: small numbers relative to the general population; racial misunderstandings—both within and without the church; anti-Adventist sentiment; and minimal resources . Yet God has used men and women of vision to establish strong roots for churches still growing today.

Ministry to African Americans on the West Coast began in earnest with Jennie Ireland, a white Bible worker, who gave Bible studies to Theodore Troy, a black postman in Furlong Tract of Los Angeles, California. The Furlong Church was organized in 1908 and stands today as the 1200-member University Church in Los Angeles.

Ten years later, those gospel roots pushed tendrils north to Seattle, Washington. Delegates to the Washington Conference Biennial Constituency Session of 1918 held a spontaneous planning session on evangelism to minority groups in the Puget Sound, including Native Americans, African Americans, Chinese and additional immigrant groups.

In response to that session, the conference executive committee voted on March 17, 1919, to hire a black minister to develop the work. A small group of African Americans meeting in the central district of Seattle was organized into a church on Sabbath, July 12, 1919, as the Lake Washington Church.

Unfortunately, the flicker of a bright future for the black work in Seattle dimmed as quickly as it had begun. The church closed in 1921. The promise of a full-time worker was to wait another 24 years for fulfillment, at the conclusion of the next World War.

In the summer of 1944, a group of African American members of the Seattle Central Church began meeting in the home of Fred and Minnie Hurd at 21st and East John streets to pray for God's guidance in reaching other blacks. Military and war effort jobs brought hundreds of black families to both the Puget Sound and Portland, Oregon. In 1945, John Osborne, pastor of the Central Church, convened a meeting of black members where their desire to form a separate congregation was expressed. They asked Fred Hurd and P. L. Nelson to present this request to the officers of the Washington Conference. In response, the conference committee voted at its June 1945 meeting to call an African-American worker to serve the Seattle group. Later that year William J. Cleveland and his wife Rita became the first pastoral couple of a black congregation in the Northwest.

Initially the congregation of 19 charter members continued to meet at the Hurd's home. But early in 1946 the conference purchased a modest building on the corner of 23rd Ave. and East Spruce Street, which, with a lot of fixing up, became the home of the Shiloh Church.

When William J. Cleveland moved from Lexington, Kentucky, to assume the pastorate of his second congregation, he met opposition from the city fathers for another black church in the city. However, when he explained the concepts of community outreach as taught by Seventh-day Adventists, that of providing a better way of life for the family and ministering to the needs of children, he gained acceptance and support from the community to begin. With the support of lay leaders such as the Hurds and Mr. and Mrs. Ben McAdoo, Cleveland was able to firmly establish the church as a beacon of hope in the community.

At the same time, the Sharon Church was beginning in the largest metropolitan area in the state of Oregon. Groundwork for the church in Portland began in 1943 when Anna Kinchon, Ann Taylor and Mozetta Noell were convicted a church to reach black people should be started. With guidance and approval from Lloyd Biggs, Oregon Conference president, they started cottage meetings and a branch Sabbath School. The group had eight members in June of 1946 when they were given company status. By October of that year they were made a church with 26 charter members and a new pastor, Preston W. McDaniels. Charter members included Shannon and Robert Goodwin, Anna Kinchon, Zetta Holly and others.

Pastor McDaniels quickly found a vacant church on the corner of Vancouver and Knott streets to rent with an option to buy. The building had a damaged roof and was in need of renovation. But it was a place to start. Members made sacrificial pledges and completed the project just in time for the church's organization on October 5, 1946.

It is evident the new congregation embraced the missionary vision of the Adventist Church and worked hard during those early years. By the end of 1948, the Sharon Church showed an increase of 53 members during their first two years of existence. Pastor McDaniels conducted evangelistic meetings with the aid of his wife, an accomplished pianist, and Justine Reed Bishop, a gifted Bible worker and singer. In those days, meetings lasted as long as 12 to 16 weeks. A flier from the 1948 meetings advertised intriguing topics, such as "Who Made the Devil," and "How Far is Hell From Portland!" The flier promised "sweet, soul-stirring music," and encouraged attendees to "come early and enjoy a great musical feast."

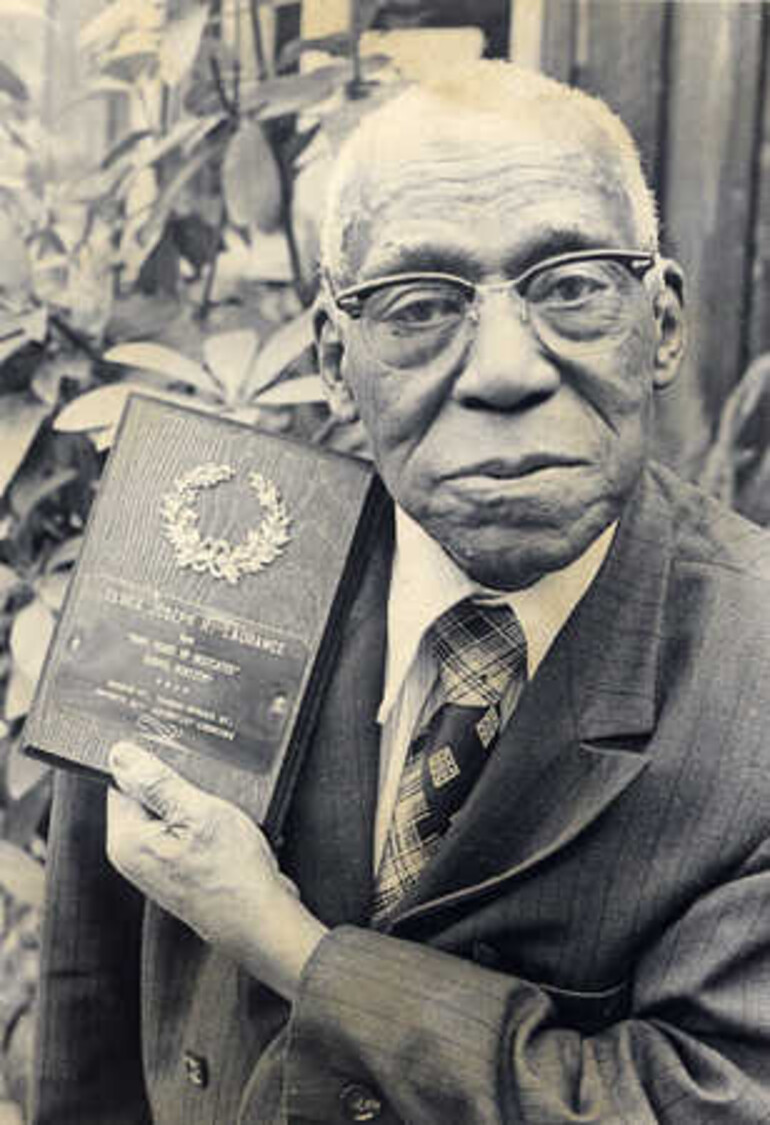

By the fall of 1950, when McDaniels accepted a call to pastor in New Haven, Connecticut, the Sharon Church had grown to nearly 100 members. J. H. Laurance, a seasoned evangelist and founding pastor of the Glenville Church in Cleveland, Ohio, was invited to run a series of meetings entitled "Revelation for our Times." Laurance, although small in stature, was a powerful and charismatic orator—preaching without notes and quoting scripture by memory. As a result of the meetings, 14 people were baptized, with many more preparing for baptism. Laurance was destined to return to the Northwest as pastor of Seattle's Shiloh Church in 1952. He soon purchased a more suitable building and changed the name of the Shiloh Church to the Spruce Street Church.

The vision of those who laid the roots of the work among African Americans in the Northwest demonstrates sustained church growth is possible when:

- Lay members meet the needs of hurting people in the community.

- Pastors put forward an active plan of personal and public evangelism.

- Colporteurs and lay Bible workers take the gospel into the homes of interested persons.

- The church exudes an attitude of loving acceptance for new and non-members.

- While we celebrate the righteous roots that have brought us thus far, we also look forward to the promise of faithful fruit today and until Jesus returns.