Editor's note: The following article was adapted from episodes 5 and 6 of How the Church Works, an Adventist Learning Community podcast. The insights from Adventist history point the way back to Christian brotherhood and unity.

Between 2016 and 2018, administrators and stakeholders of Andrews University, Southern Adventist University and Walla Walla University, heard the outcry of young Black Adventists and their allies due to racism experienced on their campuses. Though the events that sparked unrest were fairly recent, such incidences are neither isolated nor a new phenomenon in the Adventist faith community.

When Michael Brown was killed by a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri on Aug. 9th, 2014, Andrews University students led conversations on racial reconciliation and marches for racial justice through nearby Benton Harbor and St. Joseph, Michigan. The legacy of Black Adventists protesting mistreatment and oppressive systems in Adventist spaces dates back to the 1930s — and that’s just student activism.

These are just some of the most recent entries in a long history for “the push for parity,” according to Dr. Calvin Rock, Adventist historian and retired General Conference vice president. But even today, many White Adventists have a hard time seeing and understanding the ways in which Black Adventists experience racism — not only in the world, but within our own Adventist institutions, too.

Part of the reason for this lack of awareness is that, outside the Black Adventist community, Adventists don't talk enough about our roots in abolition and justice work. Many Adventists don't even know that early Adventism was also an abolitionist movement. Others know the history, and yet find it easy to claim that legacy without actually applying the theology that led our church to be abolitionists to our current context.

In order to understand what's currently happening in the Adventist Church and the larger social context of American Christianity and culture, we need to go back to the beginning — even before the Seventh-day Adventist church had officially formed.

Kevin Burton, Center for Adventist Research director and Andrews University associate professor of church history said, “All of these things about abolitionism are actually worked into our very core beliefs. It is part of our fundamental beliefs to be an abolitionist. This is vital, and it becomes even clearer when Ellen White, [an Adventist founder], responds to the fugitive slave law directly herself. She actually tells our pioneers, ‘You must break it. You must break federal law because it violates God’s law.’”

“People need to let that sink in and step back,” Burton continued. “Our prophet was telling us to break federal law? Yes, she did. And why was she doing that? Because she believed that they were living in the very end of time, and she was specifying that there would be laws that are passed by human beings at the very end of time that Adventists are going to be duty-bound to oppose and reject. And some of those laws, as she specifies explicitly, are about race.”

“It’s not just about a national Sunday law coming,” said Burton. “Adventists are not just going to have to worry about that law and having to violate those kinds of laws — they’re also going to have to violate any laws that go against God’s laws about the sanctity and full humanity of all people.”

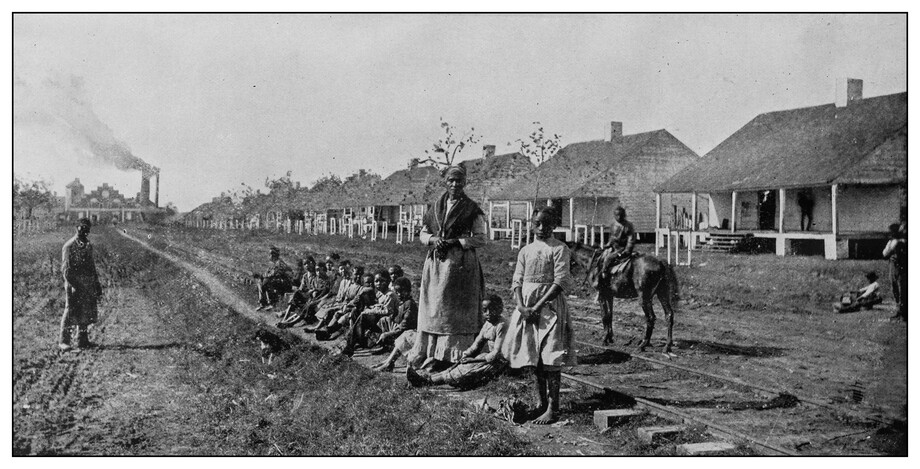

Burton estimates that only 2% of evangelical Christians at the time were abolitionists, but nearly 100% of the earliest Adventists were. The early Adventists broke all sorts of social conventions. Black and White Adventists traveled together, slept in each other’s homes, and pushed against racism both in society and within the legal system.

Nearly all early Adventists were abolitionists. They actively involved themselves in social justice.

In the early 1860s, Ellen White called to disfellowship Alexander Ross, a pro-slavery Northerner, in an effort to keep Adventism from being tainted by racist ideology. Joseph Bates, another Adventist pioneer, petitioned for his home state, Massachusetts, to abolish all of its laws that made distinctions on the basis of color.

“In order to appreciate this,” said Burton, “you have to understand that Jim Crow segregation laws were a Northern invention. Almost all White Northerners were racist to the point where they would not walk down the same side of the street with a Black person. It was serious. They would not eat at the same table or sleep in the same room or ride in the same transportation.”

Our pioneers were not afraid to engage politically on behalf of their neighbors’ wellbeing. Joseph Bates used legal means to push against segregated train cars and laws against interracial marriage. Uriah Smith, another Adventist pioneer, wrote a letter chastising Abraham Lincoln, accusing him of caring more about saving the Union than the plight of enslaved people.

In Joseph Bates’ autobiography, he wrote, “I then began to feel the importance of taking a decided stand on the side of the oppressed. My labor in the cause of temperance had caused a pretty thorough sifting of my friends, and I felt that I had no more that I wished to part with. But duty was clear that I could not be a consistent Christian if I stood on the side of the oppressor — for God was not there. Neither could I claim His promises if I stood on neutral ground. Hence, my only alternative was to plead for the slave, and thus, I decided.”

Adventist roots in anti-racist work, racial equity and social justice, though strong and genuine in their origins, did not hold against the collective onslaught of racist cultural norms and White supremacy movements in the United States over the following century. The early inclusive dreams of our pioneers eventually gave way to a hard pendulum swing toward conservative evangelical ideology. This affected our approaches to race and gender relations, creating the immediate necessity for greater independence for Black ministers, leaders and members. It ultimately caused so much damage, the Adventist Church has yet to heal.

Some Adventists express concerns about ‘getting political.’ A refresher look at our church history reveals countless examples of Adventist political activism. These include protests against big tobacco, legal work in the area of religious liberty, pro-life movements and petitions against same-sex marriage.

Claudia Allen, Howard County Government Community Outreach Division supervisor said, “I have always felt that the Adventist Church is selectively political. Because it is not that the Adventist Church does not engage in politics or that the Adventist Church doesn’t care about legislation. It’s that the Adventist Church only cares about legislation that impacts it.”

Allen went on to share examples. “So because Adventism is predominantly run by White American or White European men, their greatest fear of persecution is the Sunday Blue Law. … But then, when you talk with a Japanese Adventist who was in California when the U.S. started doing internment camps, or a Black Adventist whose family has been in America since the institution of the church and emancipation of slaves in 1863, or you talk with Hispanic and Latino Adventists — our engagement and experience with persecution is much different, and so our interest in politics is much different.”

One doesn’t have to look far to see that racism is still thriving in our country and our church. Today’s iteration of the Adventist Church has fallen a long way from the early principles that drove our pioneers. Discovering their drive for equity, justice and cross-cultural ministry requires us to look closely at our own history and denominational downfalls, as well as at the current reality and struggles of our marginalized siblings in Christ.

As Joseph Bates wrote nearly a century and a half ago, we cannot stand with the oppressive forces of our day, nor can we remain neutral to the cries of our suffering neighbors, because God is not there. Our only alternative is to join in the efforts to alleviate that suffering and to care for all of God’s children as those created in the image of God Himself.

_________________________

This article was adapted from episodes 5 and 6 of How the Church Works, a podcast written and produced by Heather Moor, Nina Vallado and Kaleb Eisele, and sponsored by the Adventist Learning Community. Written adaptation by Kaleb Eisele in partnership with the North Pacific Union of Seventh-day Adventists.