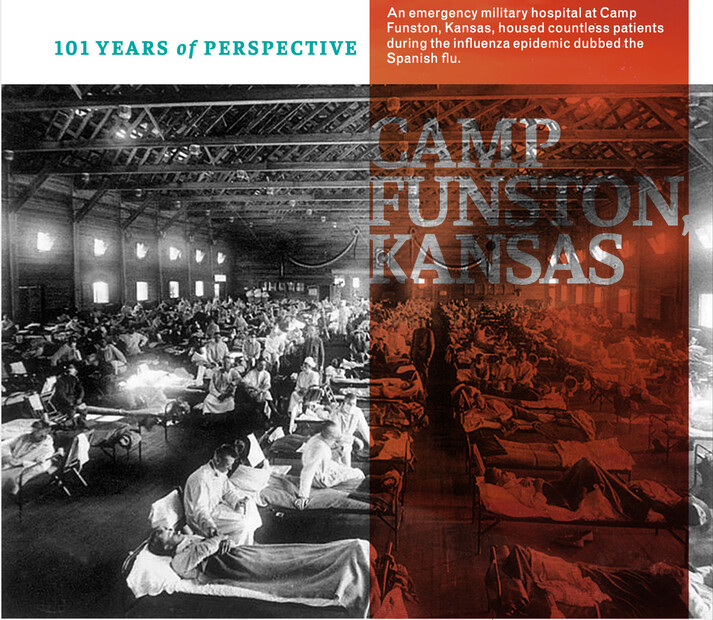

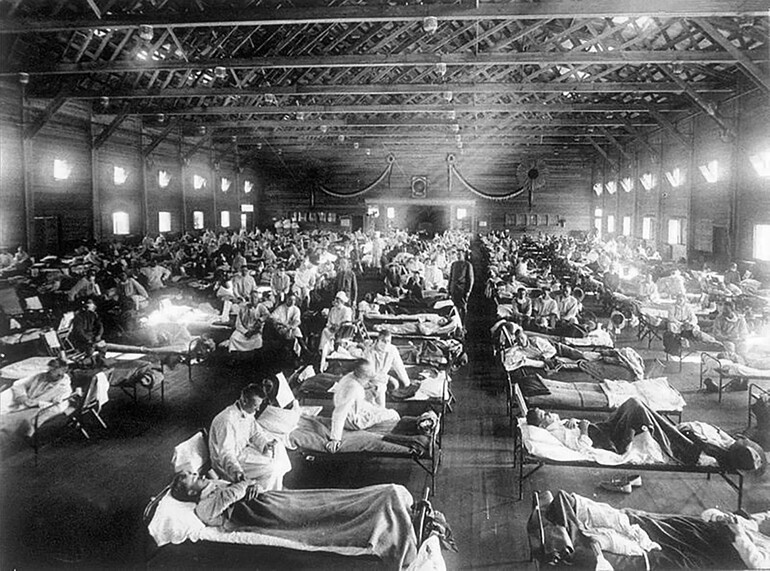

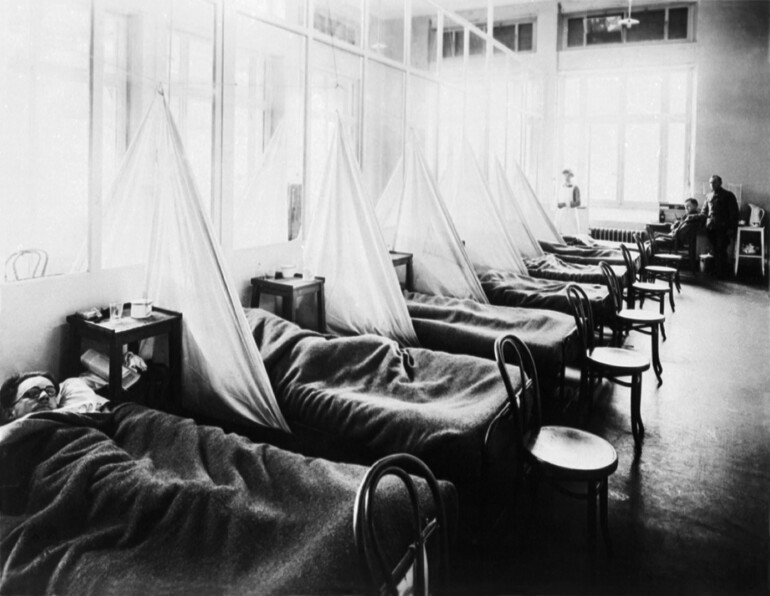

Who would have imagined a virus could close all Northwest churches in less than two weeks? And yet, 101 years ago it happened with a strain of influenza — colloquially called the “Spanish flu.”

On Oct. 5, 1918, Seattle's mayor, Ole Hanson, ordered “every place of public assemblage in Seattle, including schools, theatres, motion picture houses, churches and dance halls closed by noon,” the Seattle Daily Times reported. The front-page headline proclaimed “Epidemic Puts Ban on All Public Assemblies.”

As a result of the order, all Sabbath services were canceled for six weeks in Seattle-area churches.

The North Pacific Gleaner reported on Oct. 24, 1918, “Seattle, with many other portions of the state, is feeling the effects of the Spanish influenza. There have been thirteen or fourteen cases among the church membership thus far, but we are thankful to God that there have been no deaths, although some have been very sick. It is a new and strange experience not to be able to assemble at the house of God for worship on the Sabbath.” 1

Not only church services but Sabbath Schools were closed. The Gleaner urged families to have Sabbath Schools at home: “It is impossible now for us to meet together in our regular Sabbath schools while the quarantine is on and I am sure we all will appreciate more than ever before the blessing of the Sabbath school. ... I trust that every family will have a Home Sabbath school.”

The Adventist church school in Seattle with 70 students had to be closed as well. “The influenza epidemic has closed all schools in the city for the past two weeks. ... In spite of these hindrances, we are determined with God’s help to make this a successful year. Every pupil is cooperating with us in a most encouraging way.”

The Washington Conference committee recommended to fully support church school teachers, who already were making sacrifices: “It was voted that in view of the scourge of Spanish influenza having caused us the inconvenience of suspending the school work for the safety of our own homes, as well as the public, we recommend that our church school boards throughout the conference deal liberally with the teachers, allowing full wage for the school year. ... It is gratifying to learn that a number of churches have been paying their teachers’ salaries in full during the epidemic. It is hoped that all will do so.”

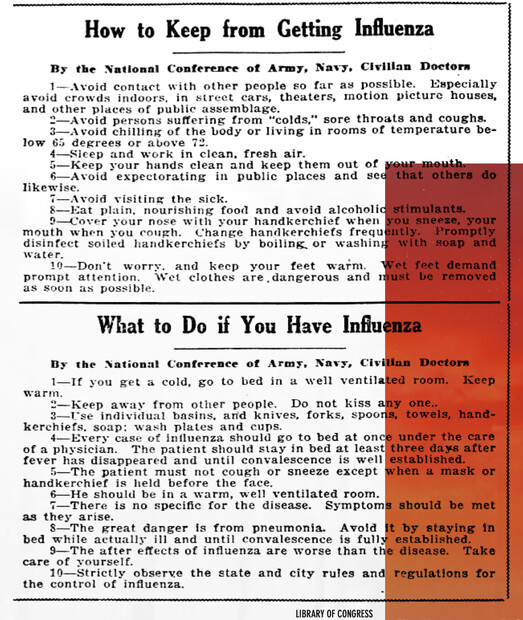

A Gleaner article by an Adventist physician, H.W. Miller, gave advice on how to avoid the flu, pointing out that most cases did not result in death and that people should exercise good hygiene practices and use other precautions. A long article gave advice that, for the most part, would be considered timely today, including that “those who have pulmonary tendencies and other general weaknesses” were especially at risk and should be careful.

Church leaders encouraged people deprived of meeting for church services to read their Bibles at home: “We will probably appreciate more fully the privilege of meeting together for worship after being deprived of our Sabbath services for a few weeks. Though we are unable to meet in public worship we have a splendid opportunity to read God’s precious word at home and to pray much for each other and the advancement of the message in the earth. Though not permitted to meet in the sanctuary, the Lord says: “I will be to them as a little sanctuary.' Eze. 11:16.”

Especially concerning was the delay of Ingathering. “The epidemic is also delaying our Harvest Ingathering campaign, but we will have to work all the harder when the ban is lifted.”

One Gleaner article urged members in eastern Washington to not neglect “laying aside our tithe and offering just as faithfully as if we were going to church every Sabbath.” An energetic church secretary in Spokane actually “has gone to homes each week and collected the Sabbath school offerings and we hear they are considerably larger than they were when the school could assemble.”

The ban on public meetings did not dissuade some evangelism from proceeding with house-to-house outreach in 1918. Today we might consider such face-to-face home evangelism to be unwise or positively dangerous: “We are visiting from house to house and giving Bible readings to those who are interested (including the distribution of Present Truth tracts). There is plenty to do along this line and we are trying to enlist the church members in this good work. One sister spends about three hours each day in missionary work for her neighbors.”

A Renton-based Adventist couple took a different tack, focusing on helping those who were ill: ”During the scourge of sickness which is visiting us here, we have given our chief attention to helping care for the sick. A number have been helped back to health.”

It is hard to overstate the seriousness of the 1918–19 influenza. The U.S. Census Bureau reports that the pandemic killed 1,513 people in Seattle (out of a 1920 Seattle population of 315,312) or 0.48%; 6,571 statewide (the state’s population was 1.373 million), also 0.48%; and 675,000 in the United States (the U.S. population was 106.5 million), or 0.63%. The total population at that time was a fraction of what it is today.

Nearly six weeks later, on November 11, 1918, the ban was lifted. Church life resumed as normal. But, sad to say, many people stricken by the Spanish flu died in the ensuing weeks and months. The Gleaner continued to report their obituaries throughout 1919.

Modern scholars tell us that an effective response to outbreaks, like the novel coronavirus (COVID-19), requires us to put aside our self-interest and use a collaborative approach. Collaboration and cooperation require a willingness to provide aid to others in need and a willingness to sacrifice personal interests.2

While these scholars make no reference to Christian charity or duty, one can't help but be reminded of the words of Jesus: "This is My commandment, that you love one another as I have loved you. Greater love has no one than this, than to lay down one’s life for his friends" (John 15:12–13).

Today churches and schools closed their doors as they did a century ago. However, we now have far greater opportunity to connect and minister through modern communication methods. In 1918, people had no access to broadcast radio or television, not to mention the internet. At the time, only 33% of Americans had telephones.3 And yet, they pulled together in the face of an unseen, unknown virus that would ultimately kill about 50 million people around the world.

In the current health crisis facing the world, may we take a lesson from our fellow Adventists a century ago, pressing together in prayer and continued service for the isolated and vulnerable among us. Now is no time to retreat.

Footnotes:

1 http://documents.adventistarchives.org/Periodicals/NPG/NPG19181024-V13-…

2 https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/handle/1805/1673

3 https://ourworldindata.org/technology-adoption