By the mid-1880s, the Seventh-day Adventist Church had established a presence in the eastern (Great Plains) and western (West Coast) portions of the American West, but was just beginning to target the more challenging regions—like the Catholic-dominated Southwest, Utah with its Mormon population, and the isolated territories of Idaho, Montana and Wyoming. In 1886, the General Conference assigned the Montana Territory to the Upper Columbia Conference, which already included the eastern portions of Washington Territory and Oregon and all of the Idaho Territory. In the next four years, this small conference with only four ministers was unable to do much to evangelize the remote Montana Territory.

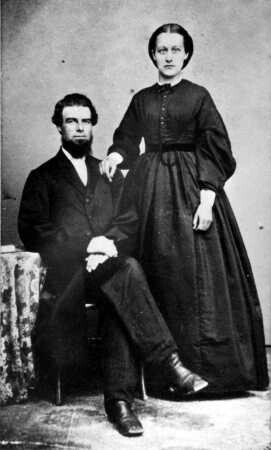

Frustrated with this slow progress, the General Conference, in 1889, made Montana a mission under their direction and the next year sent J.W. Watt to serve as the region’s first full-time minister. Watt, much like Elisha, had been called into the ministry as a young boy while plowing in a field. Several years later, he accepted Adventism in his home state of Missouri and soon became a minister.

Watt heard that Montana was a rugged country with tough people that made it a difficult place to raise a family. So he left his wife and six children in Missouri, and, for the next four years, saw his family only once a year.

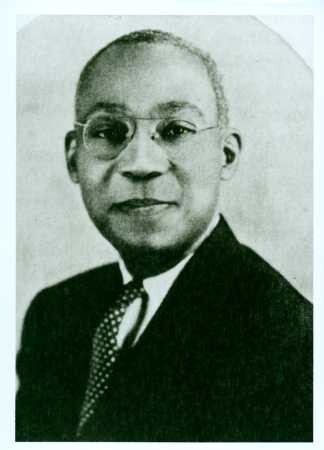

When Watt arrived in Montana, there was a small group of about 20 meeting in Livingston and a few scattered members around the state. Watt, along with an assistant from Michigan, Eugene Williams, started by conducting evangelistic meetings in the new Livingston Church. Over the next three years they held meetings and organized churches or groups in Belgrade, Bozeman, Como, Helena, Livingston and Virginia City.

One of the Livingston Church members was a wealthy rancher by the name of A.W. Stanton who generously supported the Montana Mission work. In mid-1892, Stanton visited some Adventist friends in western Washington who held fanatical views. In a letter to W. A. Colcord, Watt wrote, “Brother A.W. Stanton has concluded that he has new light for our people, and this new light is to the effect that the Seventh-day Adventist Church is Babylon, and all true believers must and will come out of her. In view of this, he has withdrawn all his financial support.”

Dan Jones of the General Conference attributed his (Stanton’s) present course more to a mental disorder than to ordinary fanaticism. Whatever the cause, Stanton left the Adventist Church.

Stanton printed a 33-page pamphlet in 1893 entitled "The Loud Cry of the Third Angel’s Message" and sent it throughout the United States. Ellen White, who was living in Australia, responded to this pamphlet with a series of articles in the Review and Herald. They were reprinted in Testimonies to Ministers and Gospel Workers, pp. 15–62.

Part of this message concerning Stanton included this well-known statement. “In reviewing our past history, having traveled over every step of advance to our present standing, I can say, Praise God. As I see what God has wrought, I am filled with astonishment, and with confidence in Christ as leader. We have nothing to fear for the future except as we shall forget the way the Lord has led us” (p. 31).

In 1894, Watt left Montana to be reunited with his family and became the president of the Indiana Conference.