Recently I watched a TED Talk during which organizational consultant Yves Morieux discusses the lack of positive change in organizations. In my estimation that includes churches. He suggests the root of our issues relate to “complicatedness.”

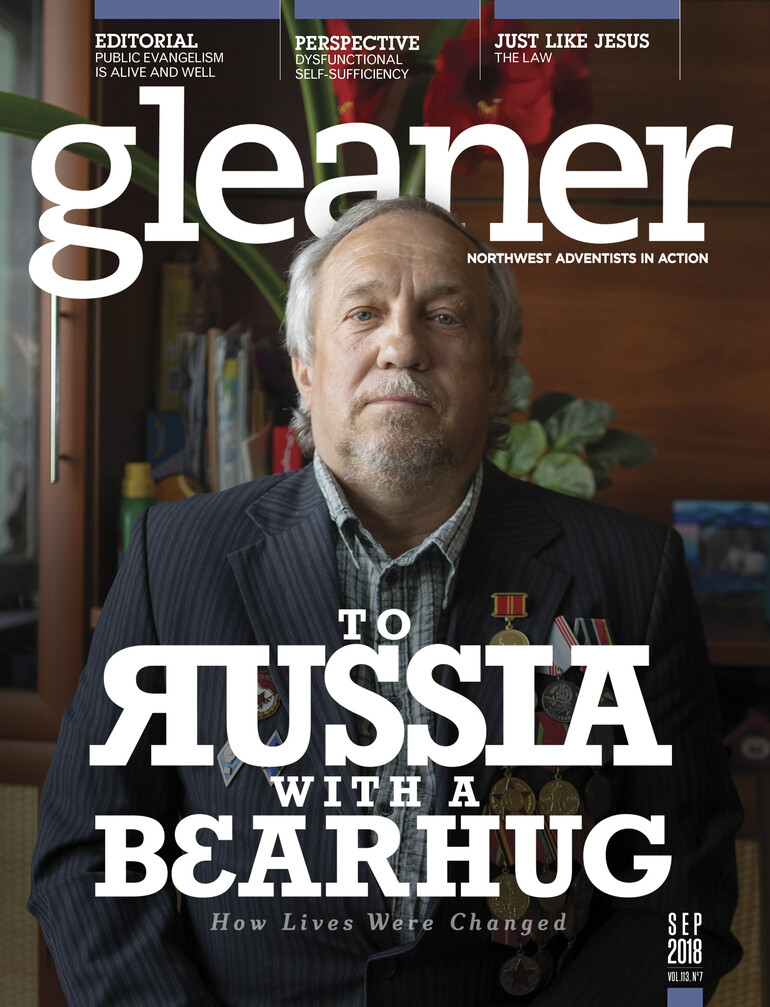

He states, “When people cooperate, they use less resources.” Conversely, when we don’t cooperate, we need more complexity and resources. Instead of building cooperation we are more likely to create more departments, positions, policies, rules, etc. The organization grows in complexity, but not efficiency or emotional health. In order to navigate the increasing complexity individuals have to operate by superhuman effort, and they burn out. This process leads to what Morieux calls “dysfunctional self-sufficiency.”

The classical biblical example is Moses trying to manage all of Israel’s issues by himself without any clear organization. Jethro, Moses’ father-in-law, sees this and has a heart-to-heart chat with Moses. Jethro says, “What you are doing is not good. You and the people with you will certainly wear yourselves out, for the thing is too heavy for you. You are not able to do it alone.” When Moses follows through and sets a better structure in place, his “dysfunctional self-sufficiency” comes to an end.

Contemporary life, especially when rooted in the individualism of social media and a Protestant tradition such as Adventism, lends itself to dysfunctional self-sufficiency. We have a hard time asking for help. We may even feel guilty about it.

In Rethinking Narcissism Craig Malkin reviews the Greek story of Narcissus who fell in love with his own reflection and died — giving us the term “narcissist.” In popular use this term refers to obnoxious self-centered people and is considered a pejorative. However, Malkin suggests narcissism is a spectrum, and it isn’t all bad.

In the story of Narcissus we have a nymph named Echo who loves Narcissus, but, alas, she has no voice of her own — she can only echo. Therefore, she never gives or receives the love she desires. Cheery story, isn’t it? Anyway, on the low end of the narcissism scale are “echoists” — those unable to speak for themselves or acquire what they need. In some ways echosim appears as arrogant as narcissism — the person who never asks for or needs help, the one who does it all, and then rages at everyone when the frayed ends of their sanity unravel.

In Adventism, at least in the West, we have a theology that is suspicious against certain forms of organized religion and that has numerous independent ministries, a sense of needing no tradition or human interference in our private interpretations of Scripture, and an American culture of “pulling ourselves up by our own bootstraps.” These things aren’t bad, but they can be a double-edged sword. Our fierce protesting Protestant spirit and our “work ethic” sometimes get in the way of asking for what we truly need and experiencing community. We are too often dysfunctionally self-sufficient.

Throughout the Bible we are told to ask what we need (Matt. 7:7–8, James 4:2–3, etc.). Morieux offers a principle I am mulling over to help create healthier organizations be they business or churches. He says, “Reward those who cooperate and blame those who don’t.” He then cites the CEO of Lego Group as stating, “Blame is not for failure; it is for failing to help or ask for help.” Blaming isn’t always helpful (see Genesis 3), but creating a culture of open communication where people don’t feel ashamed for asking for what they need is critical.

Going back to the idea of our organizations becoming so complex, with many individuals working in isolation, I wonder if the lack of simplicity in our church structures and communication practices facilitate a lack of volunteerism and ministry. Burnout is a perpetual problem in local congregations; but if people are already fiercely independent, and have no idea who to go to for help, then we create a perfect mix for dysfunctional self-sufficiency to occur. More nominating committees will need to occur and more victims … I mean volunteers … recruited to perpetuate the cycle.

These are mostly pastoral musings, but I think there are tangible elements to begin implementing. First, making people aware of these patterns and tendencies wakes them up to self-destructive practices. Second, according to Malkin, is “increase the quantity of power to use intelligence.” Giving creative voice to leaders and teams reduces complexity, which is scary for churches entrenched in control and rules. However, this shift creates a “reciprocity” where people must go to one another for help. Finally, we “extend the shadow of the future” by creating “feedback loops” where people can actually see their efforts make a difference.

Organizational complexity places people in microcosms that are disconnected from the action — how do they see the results of what they do? How do they know that what they do matters? One of Adventism’s traditional values is simplicity. Are we making church community too complex, and, if so, what might we do to empower more people to create a healthy interdependence?