It was a pleasant but breezy June day on San Francisco Bay. The steamer Oregon wove through clusters of working vessels and pleasure craft, pointing toward the center of the unbridged Golden Gate. There the voyage changed: The breeze freshened into a howling northerly wind. The ship creaked and rolled as it turned to starboard and headed north, slamming into the heavy oncoming waves, sending sheets of water over the few hardy souls shivering on deck.

Soon only a dignified, middle-aged woman remained. Her calm presence may have convinced the crew she could brave any storm. Actually, staying above deck reduced seasickness, and it was less frightening to watch the waves than to lie below imagining what they looked like. She later recalled, “… The deep … is terrible in its wrath. … I could see … God’s power in the movements of the restless waters … which tossed the waves up on high as if in convulsions of agony.”1

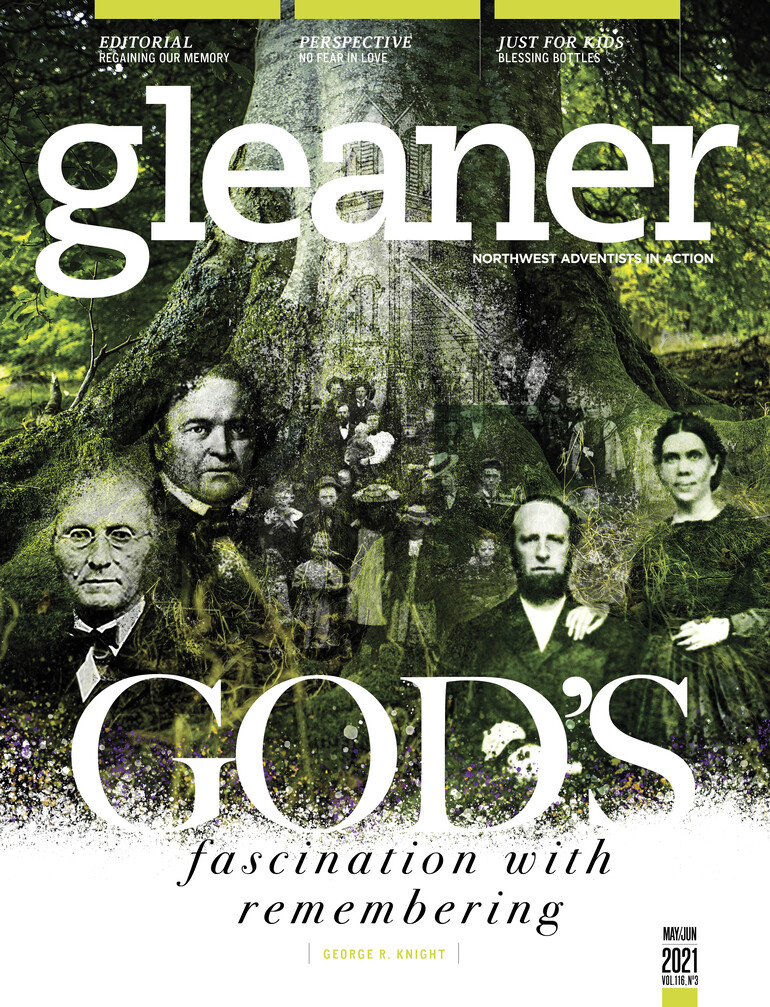

What prompted Ellen White to embark on this dangerous voyage in 1878? She was 50 years old, and constant stress had worn down her always-frail health. A trip of such magnitude wasn't an easy undertaking for a sick woman. However, she and her husband, James, had agreed that if her health stabilized, she should make this trip to Oregon to help the new churches there. When she felt strong enough for the journey, she had boarded the ship headed to Portland.

As darkness overtook the ship, the captain feared for her safety and guided her to one of the deserted public rooms where a bed was prepared for her. It was Monday evening. Seasickness overcame her as it had the others, and she stayed put until the ship moved into the calm haven of the Columbia River on Thursday morning.

As White recovered during the last few miles to Portland, she realized that both storm and seasickness had delivered a spiritual lesson: “God had spoken to my heart in the storm and in the waves and in the calm following. And shall we not worship Him?”2

White traveled on to Salem by train to attend the first Adventist camp meeting in the Pacific Northwest. It was pitched in a grove just outside of town beside the railroad. Hundreds of believers and curiosity-seekers flocked to the site. This camp meeting was a deeply spiritual experience for Northwest Adventists, and White, aided by the Holy Spirit, was the chief contributor. If she had lived an easier, less stressful life, the intensity of her inspiration would not have been the same.

Two years later, in the summer of 1880, Ellen White returned to the Northwest. The voyage was uneventful; this time the storms occurred on dry land. The work had grown impressively since her last visit — there were two camp meetings to visit — but the problems were bigger too. While White had spent her 1878 visit spiritually nourishing the fledgling church members in Salem, in 1880 she zeroed in on church leaders.

Her first stop was the Milton camp meeting. “I think there never was a place where my testimony was needed more than in this region of country,” she noted. “They seem to be deeply affected with what they hear.”3 She did not hesitate to call out the local ministers for their shortcomings. At one point she summoned conference leaders Isaac Van Horn and Alonzo T. Jones into her tent and read them the riot act.

Why couldn’t she be more, well, ladylike? In Ellen White’s camp meeting tent, Elder Van Horn and Elder Jones learned a spiritual lesson they might never have gained elsewhere. “It was a weeping, and confessing time,” White noted later. “There was a humbling of soul before God.”4 These were blunt tactics for a guest speaker to wield, particularly for a woman speaking to churchmen.

After this needed but difficult episode of spiritual training in Milton, Salem may have looked hopeful by comparison. This time the camp meeting met right in town, at Marion Square. One day White lectured the packed tent audience for two hours on the subject of temperance. More temperance sermons followed at the packed, 700-seat Methodist church nearby. White reported to James that one Methodist told an Adventist member “he regretted Mrs. White was not a staunch Methodist, for they would make her a bishop at once; she could do justice to the office.”5 At the Methodists’ request, she stayed an additional week.

Would those guest sermons have been as compelling if she had not just spent hours unraveling difficulties with church members in Milton? Something about her spiritual intensity made her message stick. This visit to Salem had a larger public dimension than the first one, and there was a larger public affirmation of her ministry.

As early Adventists were learning, the path to peace and unity was not easy. Ellen White's third and final visit to the Northwest in 1884 was the most difficult of all. James had died in 1881, and Ellen threw herself into solving all kinds of church problems. But the church in the Pacific Northwest was a problem like no other. Leaders had become harsh and critical, and they failed to inspire. The congregations had stagnated; certainly no one else would be drawn to this quarreling bunch. Northwesterners, caught up in their troubles, needed fresh eyes. So six ministers from California accompanied Ellen White on this crucial mission.

The fireworks began in Milton. Local church members met the visitors and instructed the visitors how they should preach; White recalled that she and her companions “preached the word of the Lord without any reference to their suggestions.”6 Milton Adventists yelped that they were being clubbed. The California delegation proceeded, calling church leaders forward in public, laboring with them and praying for them. Slowly, painfully, the atmosphere became more positive. As the Milton camp meeting closed, church members were once again ready to put their spiritual energies to good use.

Ellen White was exhausted. As she and her companions headed for another camp meeting in Portland to face similar problems, she developed a burning fever and was unable to leave her tent for four days. Finally, early on Friday morning, White was ready to speak. She told the assembled members they would all wait until the leading men in that region took a position that God could approve, so His Spirit could enter the meeting. “I had two front seats cleared,” she recalled later, “and asked those who were backslidden from God and those who had never started to serve the Lord to come forward. They began to come.” What happened next was unbelievable.

White reported, "Then the Spirit of God like a tidal wave swept over the congregation. … These men who had stood like icebergs melted under the beams of the Son of righteousness. … Confessions were made with weeping and deep feeling. … It seemed like the movement of 1844. I have not been in a meeting of this kind for many years. After the hard fought battle the victory was most precious. We all wept like children."7

What a transformation! The 1884 journey began in severe conflict. Failure to resolve it would have set back the church in the Northwest for decades. This difficult, stressful, wrenching situation developed into an intensely spiritual experience. In one way it resembled White’s first trip in 1878; it began in a storm, but out of suffering grew an intense blessing. The dramatic results — the once-stagnant church membership in the Pacific Northwest tripled in the next few years — occurred because church members who cared, with Ellen White at the forefront, humbled themselves before God.

Were certain things easier for Ellen White? Singled out as a visible recipient of God’s blessing, did her spiritual gifts make her more certain of the right path? How do believers with ordinary levels of spiritual giftedness find their way? Wouldn’t it be nice to know? So often it seems like groping in the dark.

When we watch Ellen White function in her own world, we see the source of her own sense of certainty was her intense, daily connection to Jesus Christ. It was a complete commitment, undertaken in 1878 at the peril of her own life and, in 1884, risking her health. Today, we might not be able to pray like Peter, preach like Paul, electrify a congregation like John Wesley or prophesy like Ellen White, but each of us can make a commitment to Jesus Christ, without reservation.

This key to this complete commitment is to give up — give up our pride, our insistence on our own way, our deep desire to stumble around alone in the dark. It happened in Salem, in Portland, in Milton and in Walla Walla over a hundred years ago, and it happened in the Great Awakening before that and at Pentecost before that. It can still happen.

1. Ellen White, Testimonies for the Church, Vol. 4 (Mountain View, CA: Pacific Press, 1948), p. 287.

3. White, "Letter 29, to J.S. White" (May 29, 1880).

5. White, "Letter 33a, to J.S. White" (June 23, 1880).

6. White, "Letter 19, to Br. and Sr. Uriah Smith" (June 15, 1884).